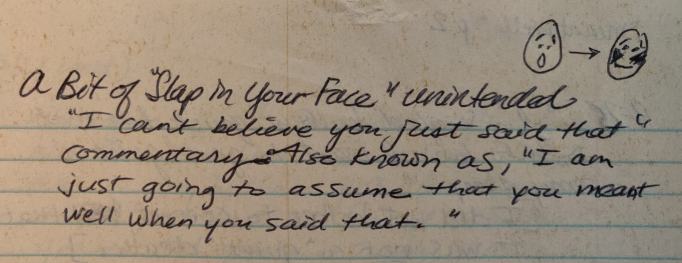

Hello, again. You might have noticed the July to April gap in new posts on What to Say When Someone Dies. Years ago, I first started writing content for this grief support website within three days of my husband’s unexpected death, although I didn’t know at the time that’s what I was doing. Even surrounded by the thick, heavy fog of shock, I recognized that some folks’ well-intended words landed like a blow to the gut or slapped me in the face.

On the other hand, a few — sadly, too few — friends’ and even strangers’ words and gestures gently reached my hurting heart through comforting compassion. I wanted to remember all these words — the helpful and the harmful — so I opened a spiral notebook and scribbled them as best I could.

As I slowly (oh, how slowly!) learned to live with my grief, I networked with widows and widowers of widely varied backgrounds, cultures, and nations, some in their senior years but many younger — even decades younger — than you’d likely expect. At the same time, I spoke at length and developed cherished friendships with bereaved parents, children, siblings, and others who mourned departed dear ones. Imagine my surprise at how many of us, while mourning diverse losses, experienced similar distressing visceral reactions to the trite, time-worn platitudes (“he’s in a better place”, “at least they didn’t suffer,” “her suffering’s over now…”) meant to offer comfort.

Likewise, regardless of our backgrounds, we appreciated the thoughtful outreach of those whose words acknowledged and validated our pain.

It took nearly three years to work up the courage to share what I learned. While my husband’s death felt recent enough to keep fresh my recollections of raw grief, the merciful yet relentless passage of time allowed me a self-preserving sliver of distance. Not only that, but in most areas of my life, I’m a deeply private person. Opening up about grief’s impact on me still sometimes feels like opening my curtains and inviting the world in to witness my vivisection.

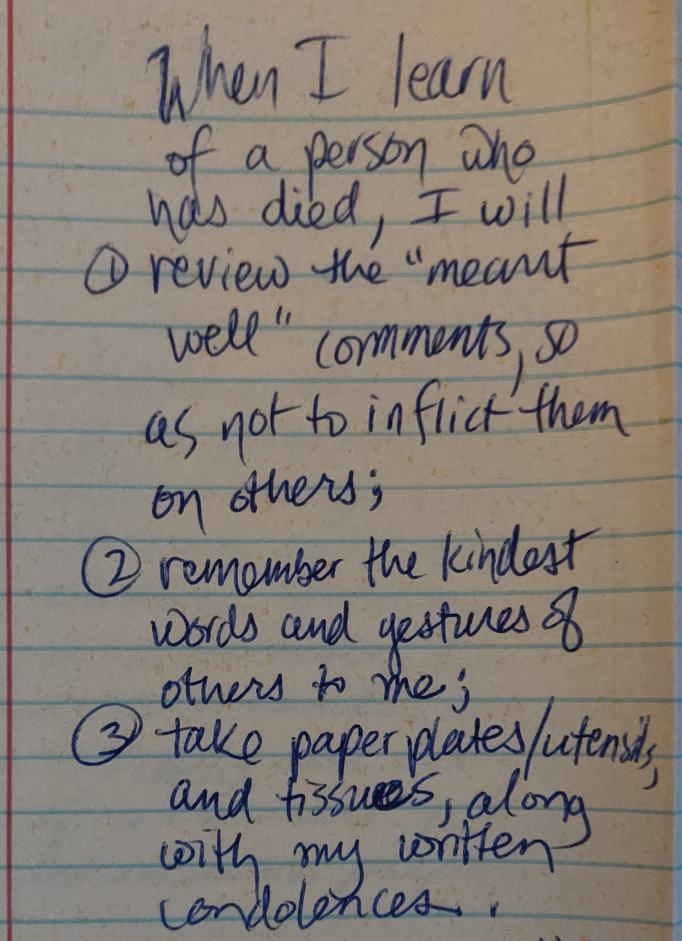

Deaths of family members and friends from December 2017 through March 2019 forced me too many times to again ask myself what to say when another someone died. New bereavement reopened wounds of mourning earlier losses. These new losses forced me to focus on how to comfort those closest to the center of each loss while grieving myself.

As much as I wanted to post here, I held back. I ached with grief, but I recognized mine wasn’t the primary loss of each surviving spouse, parent, child, or sibling. And what pain I owned felt too newly raw and too personal to publish.

For the last nine of those sixteen months, after hitting my head on the street, I’ve also been learning about managing symptoms of post-concussion syndrome. Consequently, I’ve kept my screen time focused on work for clients more than writing for myself. (Stay tuned for a post now in progress comparing the effects of grief and concussion. In true writer fashion, I tried to capture details while inside the ambulance and the MRI machine. I’ll admit those injured mental notes weren’t as coherent as I’d like.) I’m still not fully recovered, but I’ll keep working toward it.

As this website approaches the completion of its sixth year of offering ways to help grieving friends, coworkers, and family members, I remain grateful to you for reading. I’d like to thank those of you who’ve followed this content from the beginning (How I Learned What to Say When Someone Dies) as well as those of you who’ve browsed my posts only on occasion as needed. I appreciate your trust, and I’m always touched when you take the time to comment.

I hope you’ll continue to visit and share as we move forward with helping those who are grieving — and as I move forward with preparing an accompanying book.

Thank you for reading, and thank you for helping your grieving friends! — Teresa TL Bruce