This is the first post of several breast cancer awareness experiences to keep in mind during October’s breast cancer awareness month … and beyond.

Last month marked twenty years* since Mom died of breast cancer. More than thirty years ago her mother passed of the same; so did hers.

I’m therefore acutely aware of the importance of women getting regular mammograms and being vigilant about self-exams. That’s how Mom won more than three extra years with our family.

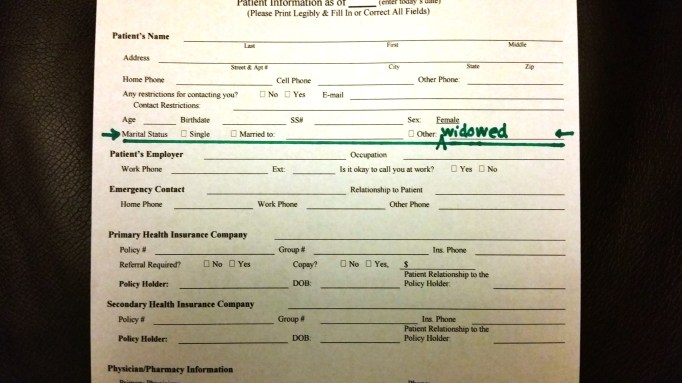

That’s why I got a mammogram — on the twentieth anniversary of Mom’s death, the week after the fifth anniversary of my husband’s.

The fun of getting a mammogram starts with stuffing top wear into a locked cubby. Photo by Teresa TL Bruce

It’s not something I look forward to every year. (Does anyone?) This year I put it off for months, until one day I finally called and made an appointment for the first available opening.

The irony of the timing didn’t hit me until that morning.

By the time I’d sat in the backed-up waiting room an hour after my scheduled appointment, my emotions were all ajumble.

By the second time the technician told me the equipment had a “technical problem” — and the procedure had to be repeated — my pertinent body parts felt all ajumble, too.

I cried — as much from emotional pain as from physical. When the technician assured me (bless her heart) that it would “only hurt for a few more seconds” (for the record, not true), she had no way to know the far deeper, longer-lasting pain came not from the contortions she inflicted on my body but from the losses the date itself smashed against my chest.

For a few moments, I plunged back into the mode of blurting my bereavement the same way I did during the early weeks (months, really) after my husband’s death.

To her credit, the woman tried to comfort me. She put an arm around me to give me a hug — but clad as I was only in the radiology center’s flimsy wraparound top, it felt awkward and uncomfortable. (In an oddly different way, the feeling reminded me how it felt when I was newly widowed and well-meaning men friends offered hugs — which at that raw time I didn’t want from any man I wasn’t related to.)

After the second round of images was taken (this time without technical difficulties), as my hand touched the doorknob, she offered a few well-intended words: “You’ll be okay. You just have to get past it. Everybody has to die sometime.”

WHAT!?

I’d just bared my soul (among other things) in front of this woman. I was crying because I missed my mom on the anniversary of her death to breast cancer, and missing my late husband, too. And she tried to make me feel better by reducing the validity of my grief? (Not to mention that she ignored my apprehension over the reason for the mammogram she’d just subjected me to.)

Yes, I saw red.

Please don’t say such things to those who are grieving! It’s true that everyone dies, but it’s not helpful or encouraging (or even nice) to make such losses seem everyday or expected or unimportant.

___

*In an earlier post I rounded up the amount of time (see https://tealashes.com/2014/06/27/comfort-after-moms-funeral/).