What do you say to someone who’s mourning a loved one before they die? What do you say to a loved one who’s dying? Although I’ve walked similar paths of anticipatory grief, each time feels like starting over because it is starting over. Each loss we mourn is unique to the relationship we have with the one who’s dying.

Should you wish someone with a terminal illness a cheerful “Happy New Year”? Maybe. Maybe not. Will your loved one likely live to see the new year come around? Will they see it but suffer further as it progresses? Perhaps a better greeting might be along the lines of “I’ll be thinking of you as the new year rolls around.”

Before Mom died

The summer when Mom’s doctors told us she had perhaps six months left to live, the rest of us thought, at first, variations on “Let’s hope she can hang on until ___,” filling in the blank with events, milestones, and holidays: my parents’ anniversary, her first grandchild’s baptism, Thanksgiving, Christmas, the birth of her next grandchild, New Year’s Day …

My mother, however, somehow knew better.

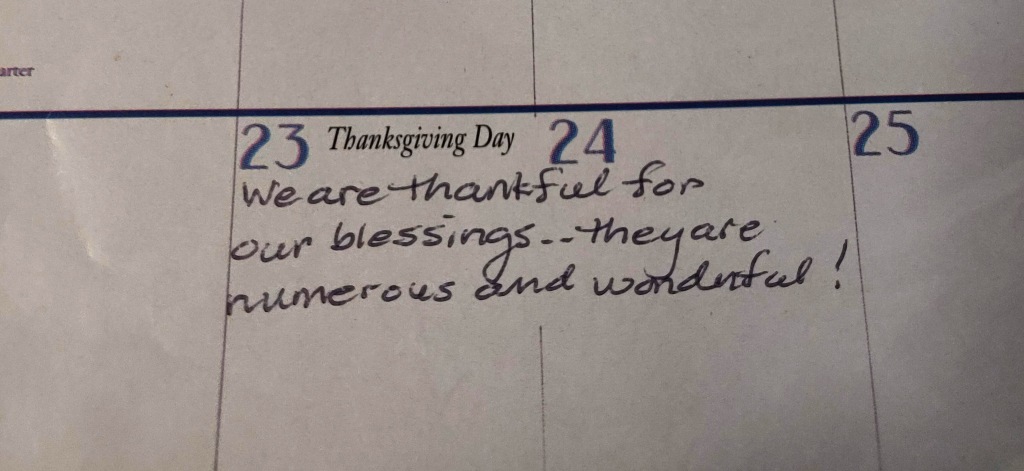

Sometime in the first three weeks after her diagnosis, while her handwriting still looked like her own, Mom penned messages onto the family calendar. When, months later, we turned the pages to November and December, we found her handwriting across the days of Thanksgiving and Christmas, days she knew she would not live to see:

Visiting the terminally ill

During the weeks of Mom’s all-too-fast yet slow terminal illness, we had plenty of time for long talks, reminiscences, and nothing-left-unsaid goodbyes.

Friends and family members came to see her and said their goodbyes as well. Some brought her goodies or magazines or flowers, but the most valuable gift they gave her was their time. Those who made their visit about her — how much they loved her, experiences they’d shared with her, and lessons they’d learned from her — brought comfort not only to her but to our whole family. And yes, they acknowledged how much they would miss her (and sometimes cried with her as they said their last goodbyes).

It was a sorrowful yet sweet, sacred time for our family.

When death strikes suddenly

My husband’s death, under much different circumstances, gave us no time — not even one minute — to prepare. Words like sudden or unexpected do little to portray the incomprehensible shock that shook us to the core. The yet-unexplained illness he suffered for a couple of years before he died had no bearing (we think) on the condition that took him without warning.

We had no chances for goodbyes or resolutions or reminiscing with him — only with ourselves.

And also with the brave, compassionate, empathetic family and friends who went out of their ways and beyond their comfort zones to sit with us in our grief, to listen to our rantings and sobbing, and to share stories of him (once we were able to let ourselves hear them). Those who helped were the ones who did not preach at us, did not tell us how to feel, and did not offer greeting-card platitudes. Instead, they sincerely sorrowed alongside us. They listened.

Another slow goodbye

Now, my family is saying another long, drawn-out, inevitable goodbye, but it’s far different than when my mom prepared to pass.

My dad is under hospice care. (I cannot praise his hospice care team highly enough. They are amazing.) The good news means he has access to health care and social workers whose compassion and experience can guide not only him but our family through this time of transition. The bad news, of course, is that qualifying to receive hospice care happens only when you are terminally ill.

My dad is terminally ill.

My dad is dying.

Bit by bit.

Slowly.

And so we mourn. Again. Sometimes with him, sometimes without.

Mourning before death

Age-related illnesses are gradually but progressively shutting down my father’s brain and body. The decades’-widowed, larger-than-life former football player who never raised his voice at me is shrinking into a different shape and temperament. Flecks of his fulfilling faith and hints of his quick humor still shine through on good days; blemishes of fear, confusion, and irrationality cover others.

My dad is still my dad, and he’s still with me, sort of. For now. At times.

But my dad is also no longer my dad, and he’s also no longer with me. Not fully. He’s here, but he’s not. He’s still living, sort of, but he’s not. I rejoice in the good moments we have together, yet I sorrow over their translucent, fleeting, fleeing reminders of what his life was compared to what his life, his end of life, is becoming.

Grieving the slow death of dementias is complicated.

Mourning the slow death of my dad is more so.

___

If you know someone impacted by any form of dementia (and the likelihood is that you do), find ways to help and encourage them through organizations like the Alzheimer’s Association and the Alzheimer’s & Dementia Resource Center.